Prohibition in Idaho, 1916 -1933

The road to Prohibition in Idaho was a bumpy one, by Arthur Hart, special to "The Idaho Statesman"

For many Americans in the 19th century, the solution to the problems associated with the use and misuse of alcoholic beverages was to prohibit their manufacture, importation, transportation or sale. Prohibition had been tried before with mixed results, first by Maine in 1846. By 1906, 18 states had tried prohibition, but only Maine, Kansas and North Dakota still had it. For the rest, enforcement had proved to be difficult, expensive and ineffective.

Local option had been somewhat more successful, allowing cities and counties to ban alcoholic beverages if the majority of their citizens voted for it, but after it went into effect, violations had been widespread. Idaho adopted local option by county in 1909. Both Gov. James H. Brady, a Republican, and his opponent Moses Alexander, a Democrat, had spoken in favor of prohibition in that year's election campaign.

"The Idaho Statesman" wrote on Sept. 7, 1909, that the campaign would end 'in a blaze of glory' and that both sides seemed confident, although the result was still 'much in doubt.' The paper asked on Sept. 8, 1909, 'Which Shall it be? If Boise goes dry today, Nampa and Caldwell will celebrate. They want a 'dry' Boise.' Miners at the Homestake mine at Neal sent word that they had a right to vote and that they would vote, 'dry forces notwithstanding.' The Teachers Institute meeting in Boise closed its session with a resolution favoring statewide prohibition. Saloon keepers at Idaho City then passed a series of humorous resolutions after receiving the news that Boise had 'stayed wet.'

Canyon County did 'go dry' in 1909, leading to a crackdown in 1910 on a private club in Caldwell. 'The Payette Club had an arrangement whereby a stock of wines and liquors was kept on hand, and the members furnished with a ticket upon payment of $1, which was punched according to the number of drinks used. The payment of another dollar bought a second ticket, and so on indefinitely, this method being thought to evade the law, as the liquor was purchased by the members as a body and kept on hand for the sole use of the members of the club.'

Prohibition kept Boise law enforcement officers busy, by Arthur Hart, Special to "The Idaho Statesman"

"Prohibition had no sooner gone into effect in Idaho in 1916, and in the rest of the country in 1920, than a significant part of the population began to look for ways to get around it. The demand for liquor was so great that tens of thousands of Americans who had never before broken any law now figured that making and selling illegal liquor was worth the risk. The Idaho Statesman reported regularly on those who got arrested for trying.

'Pullman-Auto Booze Seizure' read a headline on the morning of April 4, 1917. 'Orric Cole, proprietor of the Cole auto livery, Ray Ramsey, one of his chauffeurs, and S.H. Paterson, a Pullman porter, were arrested Monday morning at the Oregon Short Line yards at about 8:30 o'clock, just as they were about to drive off in one of Cole's autos with 44 pints of Cedar Run whiskey and two quarts of Sunnybrook that the sheriff said arrived Monday morning from Ogden in lower berth No.1.' Three suitcases were later found to contain an additional 59 pints of whiskey.

'Bootleggers Are Arrested' reported the Statesman on Aug. 18, 1917. 'Two Caught as They Cross Nevada Line; One Tries to Escape.' Some 36 cases of liquor and a four-and-a-half gallon keg of whiskey, all worth about $2,500, were seized. The men were armed with a six-shooter and a shotgun but wisely decided not to try to use them against C. A. Haskell, deputy collector for the U.S. Internal Revenue Service; Sheriff Emmett Pfost; and his deputy, Oscar Somerville. A man who tried to escape by jumping out of a moving car and running into the brush was quickly recaptured. The liquor was turned over to U.S. officials.

'Booze Cached in City Limits' was the headline on Aug. 21, 1917. Five barrels of whiskey and eight boxes of bottled beer had been driven to Boise from the area of Bruneau and hidden in brush beside the Boise River. When the young driver of the truck that brought the booze to Boise was arrested, he said he had been hired for the job by a man named Alvin Harris. He gave police a written description of his adventure: 'We got to Boise about 6 o'clock Sunday morning, August 12, after the streetcars had started to run. We came across Broadway bridge and when on the north side of Boise river turned off Broadway and onto the road that runs through Julia Davis park, followed that road about a block and a half or two blocks, then turned off toward the river, and then Harris unloaded the barrels and boxes from the truck. The place was rather swampy and tulies were growing there.' When Sheriff Emmitt Pfost and a local agent of the Department of Justice went to the spot described, they found it easily, but the booze was gone. Today's Greenbelt runs right past the spot.

A former Boise policewoman was arrested in April 1919 after beer and the apparatus for making it and 174 quarts of 1912 Old Crow and Yellowstone whiskey were found in her home near Julia Davis Park on South Ninth Street. According to Sheriff Pfost the woman brewed her beer from hops and malt in an agateware kettle on a gas range. It was then placed in a stone jar and drawn through a tube to another jar before bottling. At the time of the raid there were 20 quart bottles filled and capped.

Dozens of news items in the Statesman in the 1920s describe raids and arrests of violators of liquor laws. Boise police worked with federal, state and county officers in tracking down and arresting moonshiners and runners. In March 1921, officers arrested five men and seized three large touring cars and a light truck as they entered Idaho from Canada carrying 106 cases of bonded Canadian whiskey. In February 1926, all 13 cases on the docket of federal court in Boise were for violation of Prohibition laws. The fines meted out ranged from $200 to $500.

In 1928, 703 arrests were made in Idaho alone for violation of Prohibition laws, 86 complete stills were confiscated, 7,750 gallons of liquor and 30,020 gallons of mash were destroyed, and 25 automobiles were confiscated. And those are just for violators who got caught.

Arthur Hart writes this column on Idaho history for the Idaho Statesman each Sunday. Email histnart@gmail.com.

Prohibion in Idaho was Hard to Swallow" by Syd Albright, special to The Press ("Coeur d'Alene Press")

Idaho has always been a rough-and-tumble place, so when the federal government was pushing Prohibition nearly 100 years ago, who would think that Idaho would go along with the idea. But it did - and was that ever a mistake!

The Wild West days were pretty much over, but there was still enough lawlessness that civic-minded Idahoans thought that cutting off the supply of booze would reduce crime, increase morality, protect the young and make Idaho a healthier place to live.

That notion backfired - especially in North Idaho.

"My grandfather Rene Edward Weniger was sheriff in Shoshone County in those days, when all the bootlegging and chicanery was going on in the Silver Valley," said Gene Stone of Coeur d'Alene.

Elected in 1922, Weniger wore the badge longer than any of his 15 predecessors who waged fruitless battles to eliminate the Valley's Wild West ways - against the wishes of the valley folks who wanted to keep them.

"He was a pleasing type of personality, a fair-minded man, though he was greedy," recalled one old-timer about the popular sheriff who fearlessly told federal agents, "Stay out of my county."

Idaho approved statewide Prohibition in 1916, and National Prohibition was ratified four years later. It didn't take long for opposition to rise up however, with the French, Italians, Jewish and Basque immigrants and others hollering that drinking alcohol was part of their cultural tradition.

An argument could be made that drinking alcohol was traditional American culture as well. After all, the Pilgrims sailed to America aboard the Mayflower carrying more beer than water, and they would no doubt have happily pointed out that Jesus turned water into wine.

In 1673, Increase Mather, a Puritan minister said, "Drink is in itself a creature of God, and to be received with thankfulness." They thought that beer, wine and cider were good for everyone - including toddlers.

In colonial times, drunkenness was condemned and punished and could earn the miscreant a public whipping, a fine, or time in the stocks.

Long before anyone knew much about Idaho, whiskey was a favorite way to consume excess grain on the frontier.

In the early 1800s, people drank four times as much alcohol in America as they do today. But they drank only small portions throughout the day - during work breaks and meals - instead of binge drinking at the local pub on the way home from work.

By 1810, there were at least 2,000 distilleries producing more than two million gallons of whiskey - that by the 1820s sold for 25 cents a gallon and was cheaper than beer, wine, coffee, tea or milk.

The American Temperance Society was an important part of this history. It was founded in 1826, concurrent with a renewed religious awakening. Within 10 years, they had some 8,000 local temperance groups and 1.5 million members who campaigned for drinking in moderation, or not at all. Those who chose total abstinence wrote T. . on their pledge cards and earned the name Teetotaler.

By 1830, Americans over the age of 15 - mostly males - drank nearly seven gallons of pure alcohol a year, three times as much as today.

As America grew, people headed west and increasingly became untethered from their traditional social restraints. Taverns and inns morphed into saloons, where regard for social decorum disintegrated into drinking, gambling and barroom rowdyism.

Throughout the 19th century, the temperance forces gained momentum, leading to critical mass around the time of World War I.

Congress decided to put Prohibition to a vote as the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution requires that three-fourths of the state legislatures approve any amendment. Of the 48 states then in the Union, 46 - including Idaho - voted "yea." Connecticut and Rhode Island voted no.

Gov. Moses Alexander signed Idaho's acceptance of the law on Jan. 8, 1919. The following year, the Amendment was added to the Constitution.

Section 1 of the Amendment states: "After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited."

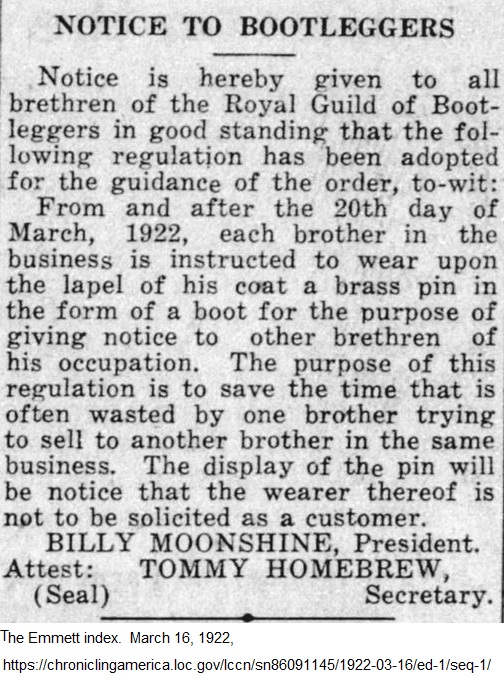

Bootleggers didn't wait for the ink to dry. Illegal stills sprouted up in hidden places all over America and the great cat-and-mouse game began, with law enforcers chasing the moonshiners, liquor smugglers and purveyors. The Idaho wilderness was ideal for hiding a still.

Since long before Prohibition, Shoshone County towns depended on funding from "liquor license" fees. After Prohibition, the fees were simply renamed as "soft drink" licenses. All "joints and vice dens," liquor stores, gambling establishments and prostitutes paid fees ranging from $15 to $25. Weniger helped collect them.

City councils did not want Prohibition laws enforced because it would dry up city funding. For law enforcement officers to do so would have been political suicide.

The Roaring Twenties and the Flapper Generation was changing the face of America with music, fun and games, speakeasies and booze. Hollywood glamorized illicit drinking, and everyone knew who Al Capone and Eliot Ness were.

It didn't take long for the new law to become unpopular.

One report said, "The criminal justice system was swamped although police forces and courts had expanded in recent years. Prisons were jam-packed and court dockets were behind in trying to deal with the rapid surge in crimes. Organized crime expanded to deal with the lucrative business, and there was widespread corruption among those charged with enforcing unpopular laws."

Idaho was quick to thumb its nose at the feds. "There was more moonshining and more illegal drinking in Idaho than just about any other state in the nation," historian Sarah Phillips wrote. "In Pocatello, there was 10-times more illegal drinking per capita than there was in Philadelphia."

Moonshiners didn't have to hide stills deep in the Idaho forests. In places like Lewiston, Pocatello and the Silver Valley, bathtubs would do just fine.

In practice, Shoshone County never did become dry, but simply acknowledged that booze was illegal. Liquor could be purchased anyplace "but the post office and Methodist Church."

During much of that time, alcohol was smuggled into Silver Valley across the mountains from Montana.

Enforcement fell to the Bureau of Prohibition, set up under the Volstead Act that backed up the 18th Amendment, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department, then later the Department of Justice.

U.S. attorney, H.E. Ray went after the Silver Valley lawbreakers, and on Nov. 11, 1929, a grand jury in Moscow "swore a complaint against soft drink proprietors, prostitutes, the entire Mullan board of trustees, Deputy Sheriff Charles Bloom, and Sheriff R.E. Weniger" for violating the National Prohibition Act.

Early on Aug. 14, 1929, the feds seized over 600 gallons of bootleg and Canadian liquor in Mullan, Wallace, and Kellogg - and the North Idaho Whisky Rebellion was on.

The feds won the court case and all the accused - including Sheriff Weniger - were convicted and sentenced to McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in Washington.

But despite all the efforts of enforcers like Eliot Ness, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover and an army of others, the illegal alcohol business thrived. By 1933, crime was rampaging nationwide, morality was declining and no health or social benefits could be seen. Life in America was becoming worse and Prohibition was a failure.

By 1933, the public had enough of Prohibition and the 21st Amendment repealed it.

The Bureau of Prohibition didn't go away however - it just eventually evolved into today's Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF).

Eighteen states still maintain some control over alcohol. Idaho is one of them, with all liquor stores run by the state government.

There are still more than 500 "dry" counties nationwide. Surprisingly, one of them is Moore County, Tenn. - home of Jack Daniels - where its popular whiskey is still not available in stores or restaurants.

Gene Stone's grandfather, Sheriff Weniger fought the verdict from his trial, never served time and was eventually pardoned.

It was much easier in the old days before Prohibition, when the sheriffs and stagecoach drivers at least didn't have to worry about arrests for drunk driving - the horses already knew their way home.

Syd Albright is a writer/journalist/biographer living in Post Falls. He is chairman of the Kootenai County Historic Preservation Commission. Contact him at silverflix@roadrunner.com.

"The Cyclopedia of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals" books.google.com

"IDAHO—In February, 1915, the Idaho Legislature passed a statutory prohibition law becoming effective January 1, 1916. This is the strictest possible law, forbidding the possession of brandy, whisky, and beer under any circumstances, and allowing wine and pure alcohol to be possessed only for sacramental and medicinal purposes. On November 7, 1916, the people of Idaho voted by about three to one for a constitutional amendment, effective May 1, 1917, fortifying the prohibition law.

"The operation of this drastic law in Idaho has been highly beneficial, according to the testimony of innumerable business witnesses. The banks show increased deposits, more legitimate goods are being sold, fewer accidents occur in the mines, and drunkenness has generally decreased.

"Mr. J. L. Ballif, Jr., of Rexburg, Idaho, calls special attention to the large number of checks now cashed in grocery and other stores, which were formerly cashed in saloons. Governor Moses Alexander declares that prohibition is almost universally approved. "We no longer even discuss it," he says. "Merchants are selling more goods, small accounts are paid promptly, working efficiency has increased, accidents in the mines are fewer than ever before, saving deposits have gone up 200 per cent, our jails are nearly empty, and police courts are idle. Here in Boise two policemen could do all of the work necessary without trouble."

Copyright © 2013 - All Rights Reserved.

Unless otherwise attributed, all photos and text are the property of Gem County Historical Society

Serving Gem County since 1973.

Hours

Wednesday - Saturday 1:00pm - 5:00pm

& by appointment :: Extended hours during The Cherry Festival in June.